The Korean War: Phase 2

16 September–2 November 1950

(UN Offensive)

Courtesy of the Center of Military History

Republished by the USASOC History Office, August 2020

Chronology

| 15 Sep | U.S. X Corps, with the 1st Marine Division, in the lead, conducts amphibious landing at Inch’on. |

| 16 Sep | U.S. Eighth Army begins its offensive northward out of the Pusan Perimeter. |

| 20 Sep | 1st Marine Division drives northeast across Han River. |

| 26 Sep | X Corps’ 31st Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division, moving east from Inch’on, links up with Eighth Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, south of Suwon. |

| 27 Sep | U.S. and Republic of Korea (ROK) forces capture Seoul, the South Korean capital. |

| 1 Oct | ROK I Corps crosses 38th Parallel and then advances up the east coast. |

| 6-7 Oct | Two ROK II Corps divisions cross 38th Parallel in central Korea. |

| 9 Oct | U.S. Eighth Army forces cross 38th Parallel north of Kaesong and attack northward toward P’yongyang, the North Korean capital. |

| 10 Oct | ROK I Corps captures the major port of Wonsan. |

| 14-17 Oct | 7th Infantry Division loads on ships at Pusan in preparation for amphibious landings by X Corps along the northeastern coast above the 38th Parallel. |

| 19 Oct | 1st ROK Division and U.S. 1st Cavalry Division capture P’yongyang. |

| 25 Oct | Communist Chinese Forces (CCF) offensive operations begin north of Unsan with fighting between CCF and ROK forces; first Chinese soldier is captured. |

| 26 Oct | 1st Marine Division, X Corps, lands at Wonsan. |

| 26 Oct | ROK forces reach the Yalu River at Ch’osan. |

| 29 Oct | U.S. 7th Division lands at Iwon. |

| 1-2 Nov | First U.S. battle with CCF, near Unsan. |

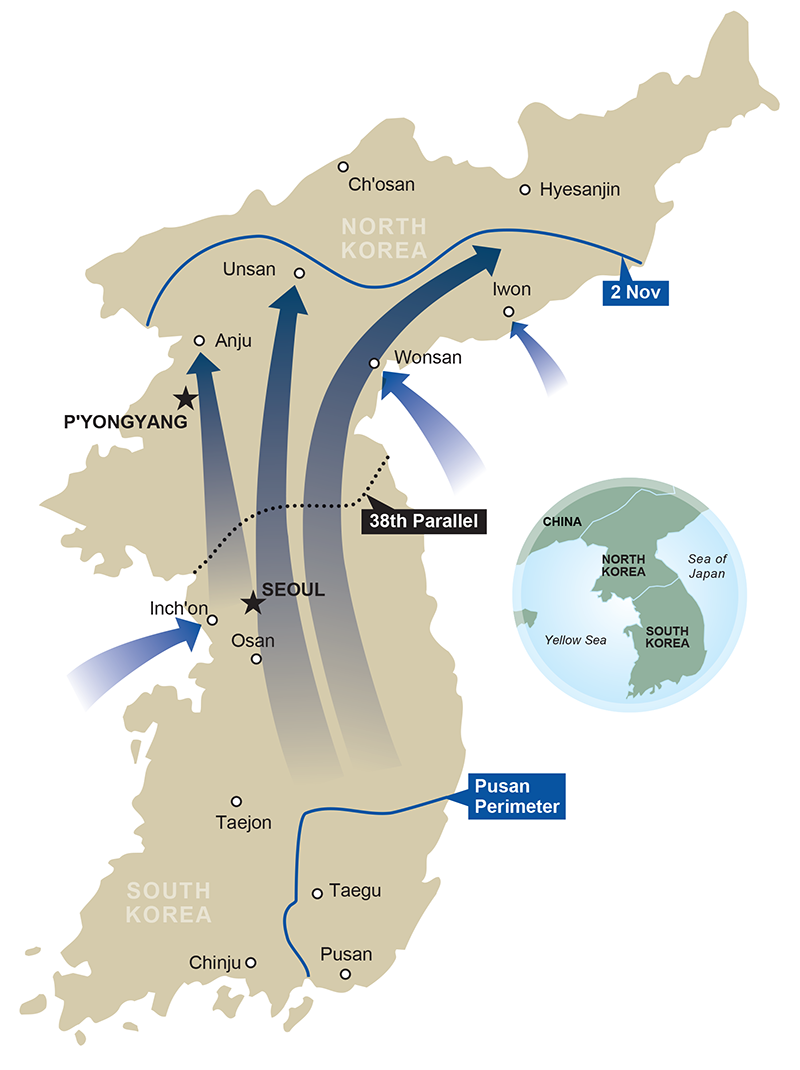

At the end of the first campaign of the Korean War, the UN Defensive, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, was ready to attempt to repel what had been the sustained advance of the North Korean People’s Army. Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker’s Eighth Army had been reinforced, its logistical support had solidified, and it had checked the enemy along a defensive perimeter west and north of Pusan. This next campaign, the UN Offensive, would be a story of stunning success.

The risk of success, however, was that it might provoke Communist China. But in mid-September 1950, Chinese military involvement was not a major concern for either General MacArthur or President Harry Truman. The focus was on breaking out from the Pusan Perimeter and engaging the North Koreans. MacArthur believed that the North Koreans’ deep penetration south into the Republic of Korea (ROK) made their forces vulnerable to an amphibious encirclement. His plan called for Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond’s separate X Corps—consisting of the 7th Infantry Division (augmented with 8,600 ROK troops) and the 1st Marine Division—to make an amphibious landing at Inch’on, a port on the Yellow Sea well behind enemy lines twenty-five miles west of Seoul. A force landing at Inch’on would have to move only a relatively short distance inland to cut North Korea’s major supply routes, recapture the South Korean capital, and block a North Korean retreat once the Eighth Army advanced northward from the defensive line at Pusan.

The landing at Inch’on was a considerable gamble. If the assault failed, MacArthur would be left with no major reserves and no prospect of immediate further reinforcement from the United States. But the landing, against light resistance, worked. Starting on 15 September when a battalion of the 1st Marine Division, covered by strong air strikes and naval gun fire, captured Wolmi Island just offshore from Inch’on, the two X Corps divisions steadily moved inland toward Seoul over the next two weeks.

Meanwhile, on 16 September the Eighth Army began its offensive. The ROK I and II Corps were positioned on the north of the Pusan Perimeter; the U.S. I Corps (composed of the 1st Cavalry Division, the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade, the 24th Infantry Division, and the ROK 1st Division) moved from the Taegu front; the U.S. IX Corps, including the 2d and 25th Infantry Divisions and attached ROK units, was poised along the Naktong River. Walker’s forces moved slowly at first, but by 23 September the envelopment threatened by X Corps and Eighth Army became clear, and the North Koreans broke to the north. Elements of X Corps’ 7th Division and of the 1st Cavalry Division, Eighth Army, linked up on 26 September just south of Suwon. Seoul was liberated the next day, and MacArthur returned the capital to President Syngman Rhee on 29 September. By the end of September the North Korean Army no longer existed as an organized force in the southern republic. The border along the 38th Parallel had been restored.

The question now was whether to cross the border. To do so would clearly risk raising tensions with China and the Soviet Union. But the North Koreans still posed a threat: some 30,000 troops had escaped from the South, and an additional 30,000 were in northern training camps. President Truman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave cautious initial approval. At the beginning of October the ROK I and II Corps crossed the 38th Parallel, moving up the east coast and through central Korea. On 9 October an all-out offensive began after the United Nations General Assembly voted for the restoration of peace and security throughout Korea, thereby tacitly approving the occupation of the North. On that day General Walker’s U.S. I Corps crossed the border on the west.

On 19 October the I Corps’ 1st Cavalry Division and the 1st ROK Division entered P’yongyang, the North Korean capital. On the 24th MacArthur ordered his commanders to advance as quickly as possible, with all forces available, so that operations could be completed before the onset of winter. The press of the Eighth Army in the west was relentless, as it sent separate columns north toward the Yalu River, each free to press forward independently. On the 26th an ROK regiment sent reconnaissance troops to the town of Ch’osan, thereby becoming the first UN element to reach the Yalu.

Meanwhile, General Almond’s X Corps had been withdrawn from combat to prepare for new amphibious landings, but this time on the east coast. The rapid advance of ROK forces above the 38th Parallel and the fall of Wonsan, North Korea’s major port, to the ROK I Corps on 10 October allowed the 1st Marine Division to make an administrative landing at Wonsan on the 26th; on the 29th the 7th Division landed unopposed at Iwon, eighty miles farther north. Adding the ROK I Corps to his command, Almond then attacked up the coast and inland toward the Yalu and the Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir, focusing on the industrial, communications, and irrigation centers of northeastern Korea. As one American newspaper put it, “Except for unexpected developments … we can now be easy in our minds as to the military outcome.”

But then the unexpected did happen. Resistance stiffened in the last week of October in both the Eighth Army and X Corps zones. On the 25th an Eighth Army ROK unit near Unsan northwest of the Ch’ongch’on River captured a Chinese soldier. The extent of Chinese infiltration was not clear, but over the next eight days Chinese forces dispersed the ROK troops who had reached the Yalu, battered the 8th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division near Unsan, and forced the ROK II Corps to retreat. Time would quickly demonstrate that this was not just a temporary setback. The nature of the Korean conflict would now fundamentally change.