“Dropping leaflets instead of parachutes and using loudspeakers instead of rifles, psychological warfare [psywar] units are ‘fighting’ side by side with airborne troopers of the [82nd Airborne] Division.” –New York Times, 15 November 19531

DOWNLOAD

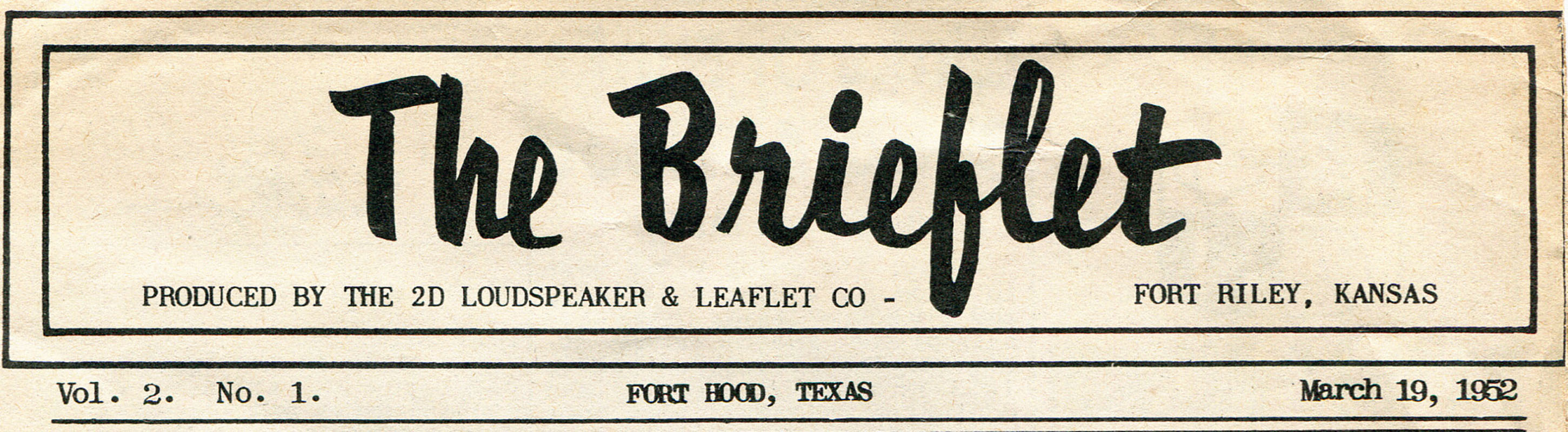

Supporting that maneuver, Exercise FALCON, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was the 2nd Loudspeaker and Leaflet (L&L) Company, a tactical psywar unit. For most of its brief existence (November 1950-February 1955), the 2nd L&L functioned as the stateside psywar training element for Army Field Forces. It thus ‘filled the gap’ left by the 1st L&L Company (formerly called the Tactical Information Detachment) when it deployed to Korea in late 1950. This article introduces the 2nd L&L in the context of renewed U.S. Army efforts to rebuild its psywar capability during the Korean War.

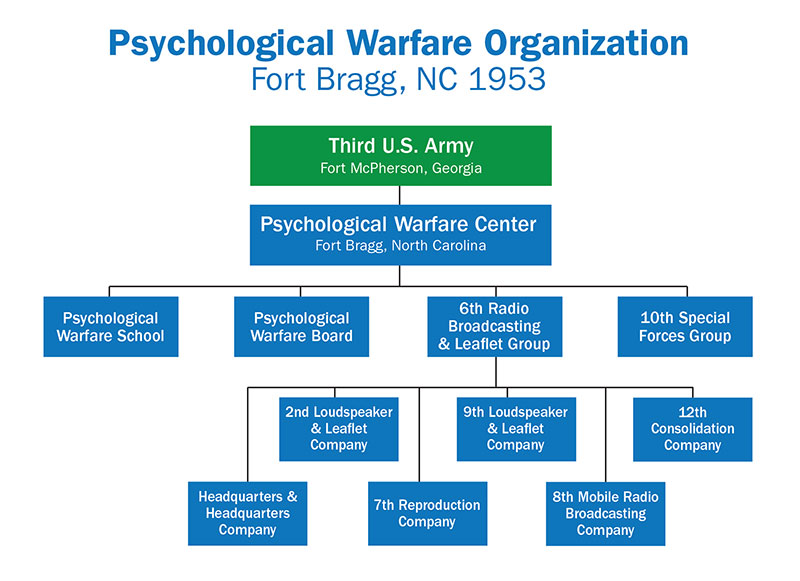

Leading the U.S. Army psywar resurgence was Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. McClure, who orchestrated the strategic psywar campaign in Europe during WWII. Heading the Psywar Division, Army G-3 starting in September 1950 and the Office of the Chief of Psywar (OCPW) after January 1951, McClure prioritized activating, manning, training, and deploying psywar units to the Far East and Europe. By spring 1951, the Army’s active duty tactical psywar inventory consisted of the 1st, 2nd, and 5th L&L Companies. The mission of these permanent, table of organization and equipment (T/O&E) units was “to conduct the tactical propaganda operations of a field army and to provide quality [psywar] specialists as advisors to the army and subordinate staffs.”2

In addition to tactical units, by spring 1951 the Army had activated the strategic 1st Radio Broadcasting and Leaflet (RB&L) Group and had federalized the U.S. Army Reserve 301st RB&L Group. These temporary, mission-driven Table of Distribution and Allowances (T/D&A) units were charged with “conduct[ing] strategic propaganda operations in direct support of military operations; support[ing] and augment[ing] the worldwide propaganda effort of the United States,” and “provid[ing] operational support to tactical propaganda units in a military theater of operations.”3

By late 1951, most of these psywar units had deployed in support of field armies and theater commands in the Far East and Europe. For Korea, the 1st L&L provided loudspeaker and leaflet support to Eighth Army while the 1st RB&L advanced U.S. and United Nations objectives with leaflets and strategic radio broadcasts. In Europe, the 5th L&L and 301st RB&L supported Seventh U.S. Army, U.S. Army, Europe (USAREUR), and the European Command (EUCOM). However, the 2nd L&L would remain stateside to train psywarriors while simultaneously orienting other units to its capabilities.

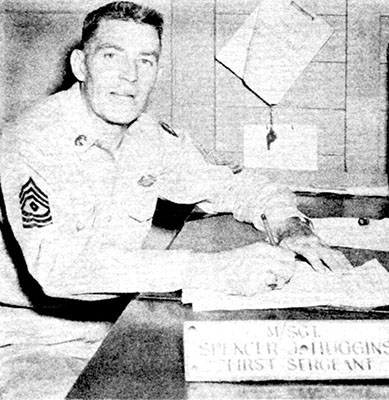

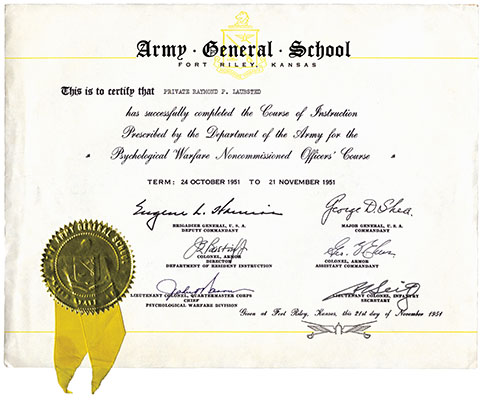

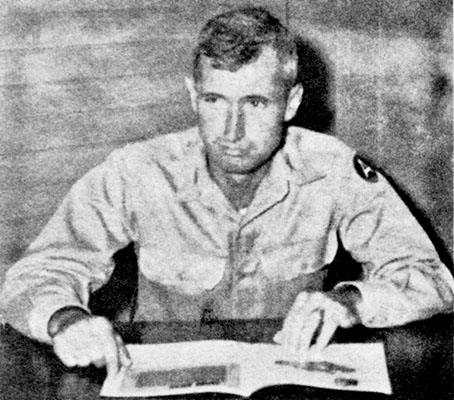

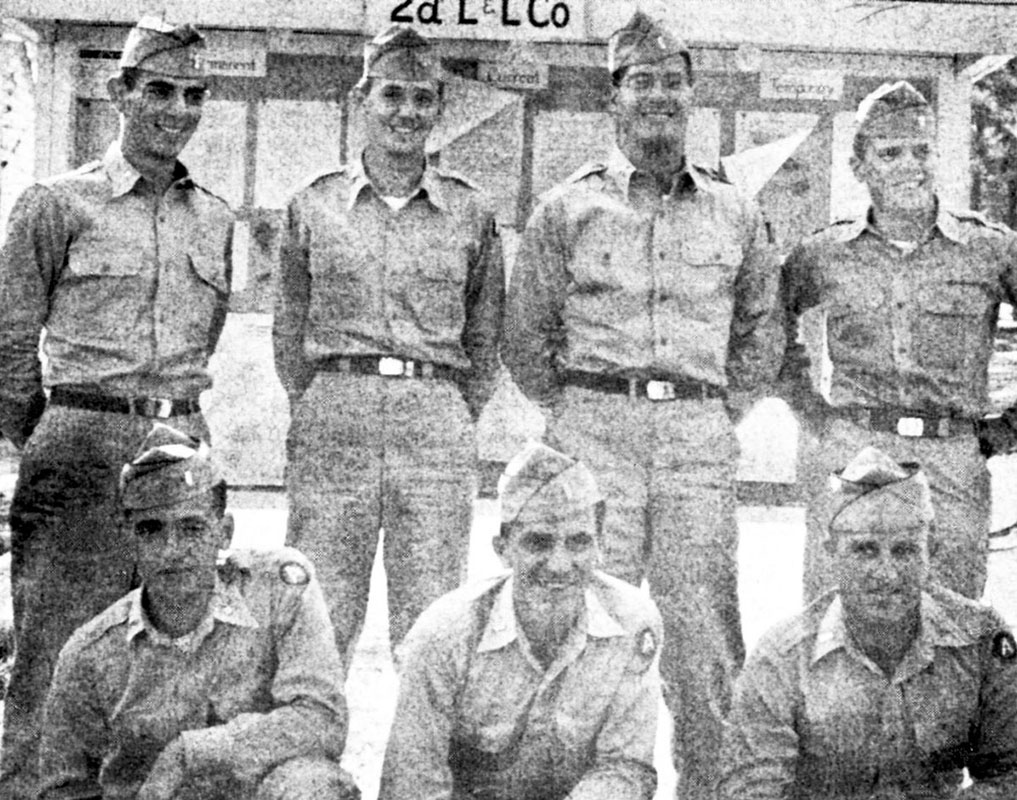

On 8 November 1950, the 2nd L&L was activated at Fort Riley, Kansas, and assigned to the Army General School (AGS). When the company submitted its first Morning Report on 6 December, it had only ten enlisted soldiers and two officers: First Lieutenant (1LT) Howard C. Walters, Jr. in command, and Second Lieutenant (2LT) William C. Shepard as the Executive Officer (XO).4 Arriving in late 1950, Corporal (CPL) Robert F. Denault recalled that soldiers “came in one at a time. We were working on getting things together to make a unit.”5 By mid-January 1951, the 2nd had grown to about forty soldiers, and by mid-June, around sixty.6

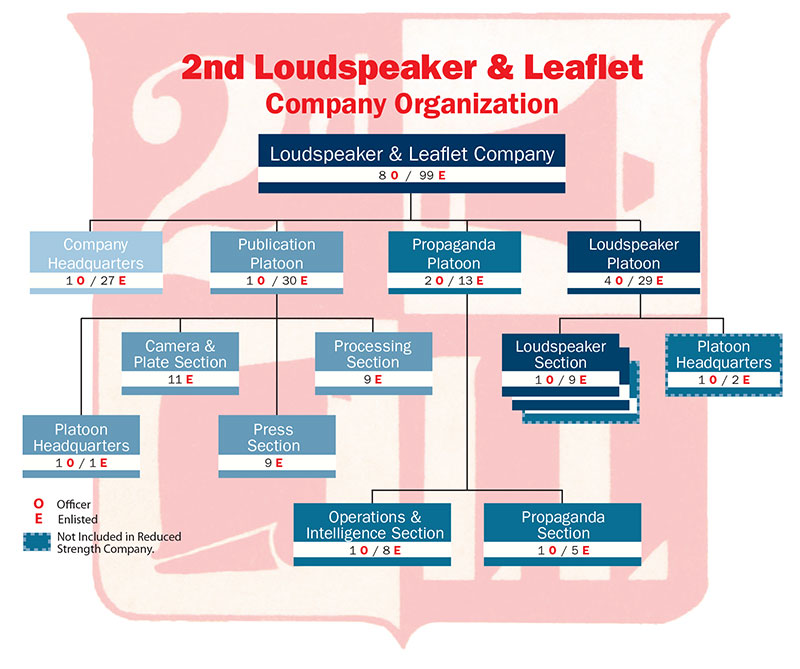

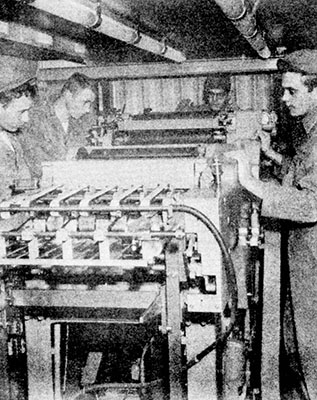

Authorized eight officers and ninety-nine enlisted men, the 2nd L&L had an initial personnel shortage, forcing it to temporarily organize as a reduced-strength company. (According to T/O&E 20-77, a reduced-strength company consisted of five officers and sixty-seven men.) However, by September 1951 the 2nd had enough soldiers to fulfill its T/O&E. It was comprised of a 28-man headquarters element to manage administration, mess, supply, training, and transportation; a 15-man Propaganda Platoon with a Propaganda Section and an Operations and Intelligence Section; a 31-man Publication Platoon with Camera, Plate, Press, and Processing Sections; and a 33-man Loudspeaker Platoon containing three Loudspeaker Sections.7 Manning these elements were soldiers with language skills, advanced education, and relevant civilian backgrounds (like printing, journalism, and advertising) who had been identified by The Adjutant General-established Classification and Analysis Center at Fort Myer, Virginia, based on criteria provided by the OCPW.