DOWNLOAD

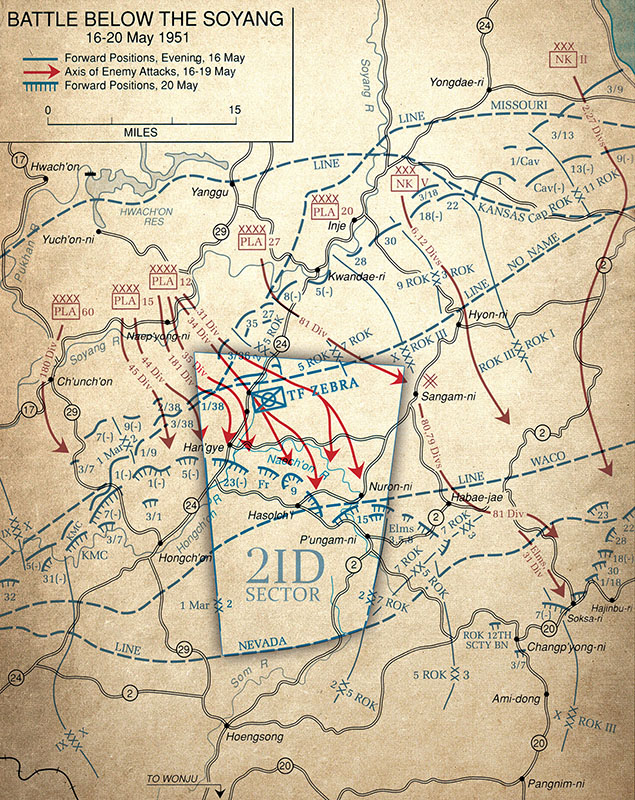

When the Chinese launched their spring offensive in April 1951, the Eighth U.S. Army defensive Line KANSAS stretched from Seoul to the east coast. The U.S. X Corps and Republic of Korea (ROK) III Corps were positioned in the eastern part. The major Chinese objective was to isolate and destroy the six divisions of the ROK III Corps. Three Chinese Armies, the 12th, 15th, and 60th and the North Korean 45th and 12th Divisions hit the ROK III Corps hard, forcing it to pull back, exposing the X Corps flank.1 The heaviest blows in X Corps fell on the right flank held by the ROK 5th Infantry Division. The 5th gave way in the face of the enemy onslaught, which triggered the withdrawal of the U.S. 7th Infantry Division in the center as well as the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division (2nd ID) on the left.

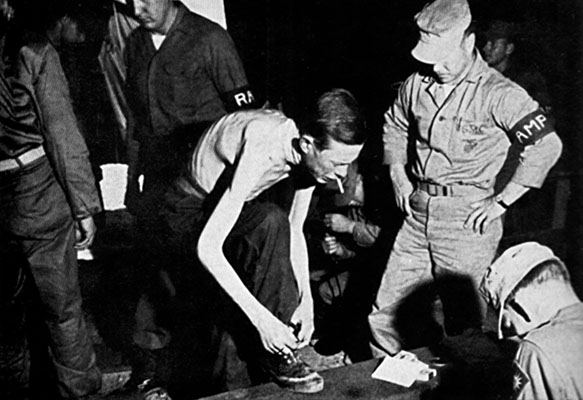

Attached to the 2nd ID, the 1st Ranger Infantry Company (Airborne) found itself in the chaotic battles around Chaun-ni on 16–19 May 1951. These actions rendered the 1st Ranger Company combat ineffective and took Staff Sergeant (SSG) Edmund J. Dubrueil out of the war. SSG Dubrueil joined 1st Ranger Company as a replacement following the battle at Chipyong-ni in February 1951. Dubrueil enlisted in the Army in 1948 and he completed Ranger training at Fort Benning, GA in January 1951. An infantry heavy weapons specialist, he was assigned to Second Platoon.2

Since its arrival in Korea in December 1950, the 1st Ranger Company enjoyed a solid working relationship with the 2nd ID. Major General (MG) Clark L. Rufner supported the need for the Rangers and made every effort to capitalize on their special capabilities.3 1st Company raided several enemy installations, including an attack on 4 February on the headquarters of the North Korean 12th Corps nine miles in the enemy rear.4 Later, at Chipyong-ni, the 1st Company acquitted themselves well in the first major defeat of Chinese forces. There the Ranger’s First Platoon, as part of an ad hoc task force containing the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, had driven the enemy off a key hilltop and re-established the main defensive line.5 Three months after the battle of Chipyong-ni, the 1st Ranger Company was fighting alongside the 23rd Regiment again, this time as part of Task Force ZEBRA.

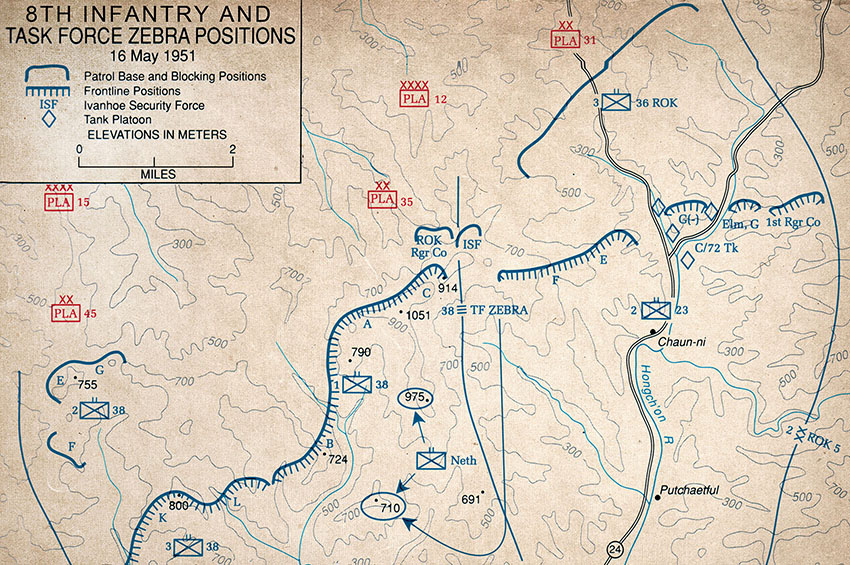

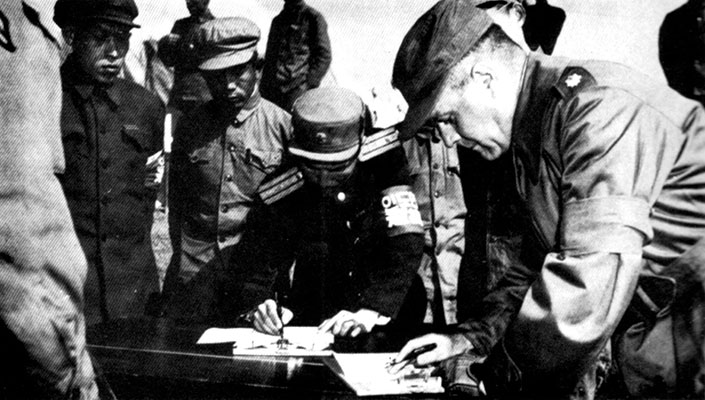

Originally formed by the 2nd ID on 25 April, at the onset of the Chinese offensive, Task Force ZEBRA was led by Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Elbridge L. Brubaker, and made up of the 72nd Tank Battalion (less one company), the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, the 1st Ranger Company, the Ivanhoe Security Force (a rear area security company of ROK troops), and the ROK 3rd Battalion, 36th Infantry Regiment. It was a formidable fighting force with considerable firepower.

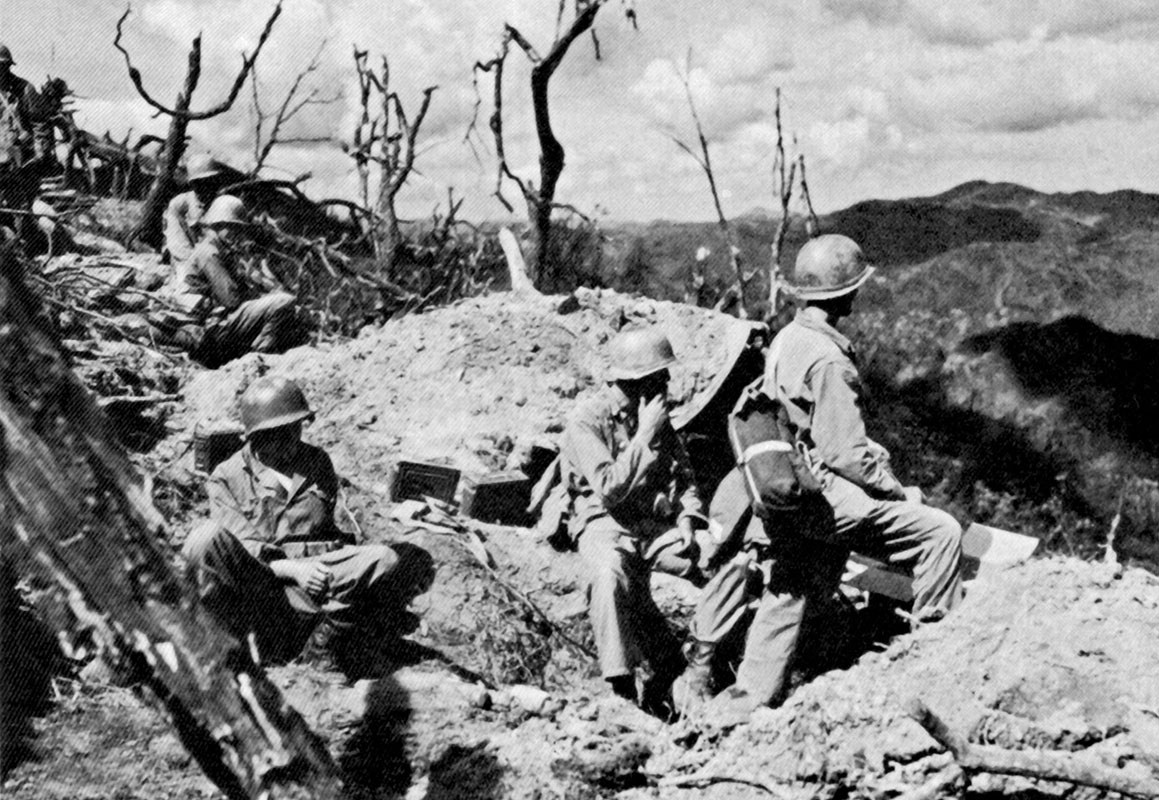

On 16 May, the Task Force was arrayed along a two-mile wide defensive position astride the Hongch’on River and Highway 24. The U.S. 38th Infantry Regiment was on the task force left and the ROK 5th Division on its right. A French infantry battalion was in reserve to the rear at Han’gye. Two key hills, 975 and 710, were occupied by a battalion of Dutch infantry and overlooked Highway 24 in Task Force ZEBRA’s area.6 When three Chinese divisions crashed into the allied lines on 16 May, the situation rapidly became critical.